|

WANDERING ALBATROSS

|

|

|

January 2 2008

Falklands - South Georgia Day 3

Position 51 57'S 47 13'W

Distance 394 nm

|

From New Island we made 4 long day sails back to Stanley, stopping to anchor in a different bay each night.

After many weeks of making short, quick hops between islands, it was a good chance to get our sea legs back before the passage to South Georgia.

The Falklands weather didn't let us down and for two days we had gale force winds, albeit with bright sunshine.

We had the pole up for much of the time and enjoyed getting the most out of the boat in the relatively protected water.

We were happy to make it back in time to celebrate Christmas Eve with good friends and over the next 2 days caught up with various friends in Stanley.

From New Island we made 4 long day sails back to Stanley, stopping to anchor in a different bay each night.

After many weeks of making short, quick hops between islands, it was a good chance to get our sea legs back before the passage to South Georgia.

The Falklands weather didn't let us down and for two days we had gale force winds, albeit with bright sunshine.

We had the pole up for much of the time and enjoyed getting the most out of the boat in the relatively protected water.

We were happy to make it back in time to celebrate Christmas Eve with good friends and over the next 2 days caught up with various friends in Stanley.

|

| |

There were only a couple of days at the end of the week when shops and services reopened between Christmas and New Year so we had a fairly busy time preparing for the next leg of the voyage.

It will be at least 3 months before we are able to take on more diesel, propane or provisions so we did a thourough stock take and loaded as much fresh fruit & veg as we could carry.

We also had to scrub the weed growth from the bottom of the boat, snorkelling in our 3mm wetsuits in the 5 degree C water - rather chilly!

The long range weather forecast was showing a week of relatively consistent weather, with winds up to 25 knts and it looked like as good a gap as we could hope for to set out on the 800 mile passage to South Georgia.

By Sunday morning we were making final checks, stowing the last bits and pieces and saying our farewells.

The time in the Falklands has been very memorable and we know we'll be back one day.

Motoring out through the Narrows for the last time the friendly little Commersons dolphins came to play in our bow wave as we set the sails and headed east.

There were only a couple of days at the end of the week when shops and services reopened between Christmas and New Year so we had a fairly busy time preparing for the next leg of the voyage.

It will be at least 3 months before we are able to take on more diesel, propane or provisions so we did a thourough stock take and loaded as much fresh fruit & veg as we could carry.

We also had to scrub the weed growth from the bottom of the boat, snorkelling in our 3mm wetsuits in the 5 degree C water - rather chilly!

The long range weather forecast was showing a week of relatively consistent weather, with winds up to 25 knts and it looked like as good a gap as we could hope for to set out on the 800 mile passage to South Georgia.

By Sunday morning we were making final checks, stowing the last bits and pieces and saying our farewells.

The time in the Falklands has been very memorable and we know we'll be back one day.

Motoring out through the Narrows for the last time the friendly little Commersons dolphins came to play in our bow wave as we set the sails and headed east.

|

| |

For the first 2 days we were treated to light wind from the north or northwest and although this meant we made quite slow progress it also meant we could settle gently into the routine of the passage.

With full sails flying, including the staysail, we were gliding along at about 4 knots in remarkably calm seas.

Clear skies brought long sunny days and short, star-studded nights with beautiful sunrises (see photo) and sunsets.

But the Southern Ocean never sleeps for long and last night things began to change, with the wind increasing to around 25 knots, requiring a reefed main and jib.

The sea has picked up quickly and now we are charging along with the wind on the quarter and a constant procession of grey, tumbling waves pushing us forward.

There has been heavy fog all day today along with spells of light drizzle.

A new depression is forming just south of the Falklands and should pass south of us tomorrow, intensifying as it goes.

For the first 2 days we were treated to light wind from the north or northwest and although this meant we made quite slow progress it also meant we could settle gently into the routine of the passage.

With full sails flying, including the staysail, we were gliding along at about 4 knots in remarkably calm seas.

Clear skies brought long sunny days and short, star-studded nights with beautiful sunrises (see photo) and sunsets.

But the Southern Ocean never sleeps for long and last night things began to change, with the wind increasing to around 25 knots, requiring a reefed main and jib.

The sea has picked up quickly and now we are charging along with the wind on the quarter and a constant procession of grey, tumbling waves pushing us forward.

There has been heavy fog all day today along with spells of light drizzle.

A new depression is forming just south of the Falklands and should pass south of us tomorrow, intensifying as it goes.

|

| |

There has been a fantastic number of birds around: tiny storm petrels dance and flutter in our wake; prions twist and turn in flashes of blue-grey; and the albatrosses glide past.

Black-browed, grey-headed, Wandering and Royal albatrosses have all been spotted.

The first 3 all breed at South Georgia but the Royal albatross breeds only in New Zealand, on the opposite side of the world.

All those we've seen have been immature birds, which may circumnavigate the Southern Ocean before returning to breed.

In the lighter air, the albatrosses struggle to stay airborne as they need the lift of the wind to set them soaring.

The Black-brows in particular seem to be attracted to the boat, often swooping close and landing with an ungainly splash just off the stern (see photo).

There has been a fantastic number of birds around: tiny storm petrels dance and flutter in our wake; prions twist and turn in flashes of blue-grey; and the albatrosses glide past.

Black-browed, grey-headed, Wandering and Royal albatrosses have all been spotted.

The first 3 all breed at South Georgia but the Royal albatross breeds only in New Zealand, on the opposite side of the world.

All those we've seen have been immature birds, which may circumnavigate the Southern Ocean before returning to breed.

In the lighter air, the albatrosses struggle to stay airborne as they need the lift of the wind to set them soaring.

The Black-brows in particular seem to be attracted to the boat, often swooping close and landing with an ungainly splash just off the stern (see photo).

|

| |

January 6 2008

Arrived in South Georgia

Position 54 02'S 37 58'W - Anchored in Elsehul Bay

Distance 778 nm

|

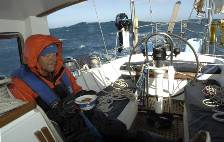

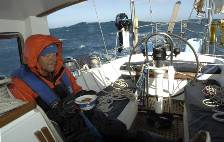

On the evening of our third day out from the Falklands the barometer began to drop rapidly as a small but deep depression approached.

With the GRIB forecast indicating windspeeds up to 50 knots as the low moved east and intensified, we made the decision to heave to for about 8 hours to let it slide below us.

Even so, by early the next morning we had a strong gale with gusts to 48 knots and large, tumbling seas.

We had reduced sail to the triple reefed main, which is smaller than the trisail specified for our boat, and a double furled staysail.

Running downwind we were doing well over 7 knots and surfing up to 9 knots in the powerful swell.

We took shelter under the doghouse as much as possible, eating bowlfuls of hot porridge, the easiest thing to cook in those conditions!(see photo)

On the evening of our third day out from the Falklands the barometer began to drop rapidly as a small but deep depression approached.

With the GRIB forecast indicating windspeeds up to 50 knots as the low moved east and intensified, we made the decision to heave to for about 8 hours to let it slide below us.

Even so, by early the next morning we had a strong gale with gusts to 48 knots and large, tumbling seas.

We had reduced sail to the triple reefed main, which is smaller than the trisail specified for our boat, and a double furled staysail.

Running downwind we were doing well over 7 knots and surfing up to 9 knots in the powerful swell.

We took shelter under the doghouse as much as possible, eating bowlfuls of hot porridge, the easiest thing to cook in those conditions!(see photo)

|

| |

Things began to calm down later in the day and the skies cleared to give us a wonderful, frosty night.

The sea temperature had been dropping steadily as we began to cross the Antarctic Convergence Zone, which sweeps up in a big loop from further south.

When we left the Falklands the water was around 5 degrees C but now it was almost zero.

With the chances of encountering ice becoming ever more likely, we hove to for the 6 hours of darkness, reducing our boatspeed to a mere 1.5 knots while riding comfortably in the choppy sea.

But it wasn't until the following afternoon that we spotted our first large iceberg (see photo), a giant slab at least 100 feet above the water and about a quarter of a mile long, probably broken from an ice shelf in the Weddell sea and brought up here on the current.

From then on there was always a berg or two within a few miles of us and although the large bergs show up well on the radar, pieces the size of the boat and smaller were lost in the sea clutter on the screen.

We had to keep a constant and vigilant look out and the final 24 hours of the passage were exhausting.

Thick fog made watching for ice quite tricky - every breaking wave looked like a chunk of ice and chunks of ice got hidden amongst the breaking waves.

Things began to calm down later in the day and the skies cleared to give us a wonderful, frosty night.

The sea temperature had been dropping steadily as we began to cross the Antarctic Convergence Zone, which sweeps up in a big loop from further south.

When we left the Falklands the water was around 5 degrees C but now it was almost zero.

With the chances of encountering ice becoming ever more likely, we hove to for the 6 hours of darkness, reducing our boatspeed to a mere 1.5 knots while riding comfortably in the choppy sea.

But it wasn't until the following afternoon that we spotted our first large iceberg (see photo), a giant slab at least 100 feet above the water and about a quarter of a mile long, probably broken from an ice shelf in the Weddell sea and brought up here on the current.

From then on there was always a berg or two within a few miles of us and although the large bergs show up well on the radar, pieces the size of the boat and smaller were lost in the sea clutter on the screen.

We had to keep a constant and vigilant look out and the final 24 hours of the passage were exhausting.

Thick fog made watching for ice quite tricky - every breaking wave looked like a chunk of ice and chunks of ice got hidden amongst the breaking waves.

|

| |

On our last night out the wind picked up again to about 30 knots and we both had to stay up through the hours of darkness to peer into the gloom for ice.

Another depression was forming to the west of us and deepening as it approached South Georgia so we pushed hard to reach the shelter of Elsehul bay at the western end of the island before dark.

All day the fog cocooned us and we didn't so much as glimpse our landfall until we were just a few miles off the coast.

The swirling grey mist lifted a fraction to reveal jagged black rocks and steep cliffs, a rather forbidding sight in the fading light.

Then one after the other a Wandering albatross, a Black-browed albatross, a Grey-headed albatross and a Sooty albatross, the 4 species that nest here, soared out of the fog ahead and circled the boat as if inspecting us.

A loud blow sounded behind us and we turned just in time to catch a glimpse of a big male Killer Whale as it sank back beneath the surface.

And all around us the sleek shapes of fur seals porpoised and rolled, their pointed snouts constantly popping up above the water to have a look at us.

Surrounded by this amazing wealth of wildlife we furled the jib and motored into the outer bay of Elsehul to drop the main.

The mist was lifting all the time and towering buttresses of rock dwarfed us, the great folds of countless sedimentary layers etched in a dusting of fresh snow.

A mournful and haunting wail filled the air, echoing off the cliffs and we realised it was the calls of the thousands of fur seals that lined every available inch of shoreline.

It was like a chorus of baying hounds, yowling cats and cheering fans all at once.

The overall impression was of having sailed back to the beginning of the world, a primeaval scene of raw and powerful nature at work, uncompromising but thrilling.

It was certainly a memorable landfall and a wonderful feeling to drop the anchor in the inner bay at very last light last night.

This morning dawned dull and sleety (see photo) with the wind whistling overhead and buffeting us with violent gusts as the low passed over.

We will sit tight here until conditions improve for the 70 mile sail along the coast to Grytviken where we must check in with the Government Officer...

On our last night out the wind picked up again to about 30 knots and we both had to stay up through the hours of darkness to peer into the gloom for ice.

Another depression was forming to the west of us and deepening as it approached South Georgia so we pushed hard to reach the shelter of Elsehul bay at the western end of the island before dark.

All day the fog cocooned us and we didn't so much as glimpse our landfall until we were just a few miles off the coast.

The swirling grey mist lifted a fraction to reveal jagged black rocks and steep cliffs, a rather forbidding sight in the fading light.

Then one after the other a Wandering albatross, a Black-browed albatross, a Grey-headed albatross and a Sooty albatross, the 4 species that nest here, soared out of the fog ahead and circled the boat as if inspecting us.

A loud blow sounded behind us and we turned just in time to catch a glimpse of a big male Killer Whale as it sank back beneath the surface.

And all around us the sleek shapes of fur seals porpoised and rolled, their pointed snouts constantly popping up above the water to have a look at us.

Surrounded by this amazing wealth of wildlife we furled the jib and motored into the outer bay of Elsehul to drop the main.

The mist was lifting all the time and towering buttresses of rock dwarfed us, the great folds of countless sedimentary layers etched in a dusting of fresh snow.

A mournful and haunting wail filled the air, echoing off the cliffs and we realised it was the calls of the thousands of fur seals that lined every available inch of shoreline.

It was like a chorus of baying hounds, yowling cats and cheering fans all at once.

The overall impression was of having sailed back to the beginning of the world, a primeaval scene of raw and powerful nature at work, uncompromising but thrilling.

It was certainly a memorable landfall and a wonderful feeling to drop the anchor in the inner bay at very last light last night.

This morning dawned dull and sleety (see photo) with the wind whistling overhead and buffeting us with violent gusts as the low passed over.

We will sit tight here until conditions improve for the 70 mile sail along the coast to Grytviken where we must check in with the Government Officer...

|

| |

January 12 2008

Grytviken

|

After an enforced day of rest in Elsehul as we sat out another gale we got underway early on the 7th to sail the 70 or so miles along South Georgia's north coast to the settlement at Grytviken.

We broke the journey into 2 legs, stopping halfway in Blue Whale Harbour, and for both sailing days we had moderate northwest wind which allowed us to put the pole up and rock along in the big Southern Ocean swell with goose-winged sails (see photo).

We were treated to some beautiful weather and had a taste of South Georgia's gentler side with fantastic views towards the vast, snow capped mountain ranges of the interior.

Albatrosses soared past constantly and fur seals porpoised ahead of the bow in a sea of clear aquamarine.

The island has a special magic and we felt it casting its spell over us straight away.

After an enforced day of rest in Elsehul as we sat out another gale we got underway early on the 7th to sail the 70 or so miles along South Georgia's north coast to the settlement at Grytviken.

We broke the journey into 2 legs, stopping halfway in Blue Whale Harbour, and for both sailing days we had moderate northwest wind which allowed us to put the pole up and rock along in the big Southern Ocean swell with goose-winged sails (see photo).

We were treated to some beautiful weather and had a taste of South Georgia's gentler side with fantastic views towards the vast, snow capped mountain ranges of the interior.

Albatrosses soared past constantly and fur seals porpoised ahead of the bow in a sea of clear aquamarine.

The island has a special magic and we felt it casting its spell over us straight away.

|

| |

Grytviken lies in protected King Edward Cove off Cumberland East Bay (see photo), a deep fjord cutting into the island about half way along the north shore.

Hemmed in by steep scree covered mountains with the distant snow frosted peaks of Mt Paget and Sugartop soaring over 7000 feet the setting is spectacular.

At King Edward Point a British Antarctic Survey base supports a number of scientists and it was here that we tied up briefly while Emma, the Government Officer, came on board to run through the formalities.

Over cups of tea in the cockpit, she issued us with our permit to sail around the island and explained various regulations, mostly concerned with protecting this unique environment and preventing the spread of invasive plant species, avian diseases and rats.

Grytviken lies in protected King Edward Cove off Cumberland East Bay (see photo), a deep fjord cutting into the island about half way along the north shore.

Hemmed in by steep scree covered mountains with the distant snow frosted peaks of Mt Paget and Sugartop soaring over 7000 feet the setting is spectacular.

At King Edward Point a British Antarctic Survey base supports a number of scientists and it was here that we tied up briefly while Emma, the Government Officer, came on board to run through the formalities.

Over cups of tea in the cockpit, she issued us with our permit to sail around the island and explained various regulations, mostly concerned with protecting this unique environment and preventing the spread of invasive plant species, avian diseases and rats.

|

| |

With the paperwork complete, we relocated to a wooden dock in the inner harbour.

It felt good to tie up and know that we didn't have to worry about the weather for at least the next few days and we had our first good night's sleep since leaving the Falklands!

We awoke the next day to find it snowing heavily and everything but the immediate surroundings was lost in a haze of white.

But it was too warm for it to last long and soon it turned to a misty drizzle.

We found ourselves sharing the dock with a young elephant seal which burbles and bumps beneath the hull every morning and occasionally hauls out on the jetty (see photo).

With the paperwork complete, we relocated to a wooden dock in the inner harbour.

It felt good to tie up and know that we didn't have to worry about the weather for at least the next few days and we had our first good night's sleep since leaving the Falklands!

We awoke the next day to find it snowing heavily and everything but the immediate surroundings was lost in a haze of white.

But it was too warm for it to last long and soon it turned to a misty drizzle.

We found ourselves sharing the dock with a young elephant seal which burbles and bumps beneath the hull every morning and occasionally hauls out on the jetty (see photo).

|

| |

We were right in the middle of the old Grytviken whaling station, surrounded by the rusting remains of huge boilers, whale oil storage tanks and machinery.

The station operated between 1904 and 1965 and was on a large and profitable scale.

Seen from above it has the appearance of a small village (see photo) and in its heyday supported up to 300 workers.

This was the first shore-based whaling station in the Antarctic region but more soon followed with similar stations built at Husvik, Stromness, Leith and Prince Olav.

Some 175,000 whales were caught and processed in the 60 year period of whaling around South Georgia.

Although interesting, we found the whaling station a bit depressing, a testament to man's greed and cruelty as well a monument to human endeavour and determination to succeed in a harsh environment.

We were right in the middle of the old Grytviken whaling station, surrounded by the rusting remains of huge boilers, whale oil storage tanks and machinery.

The station operated between 1904 and 1965 and was on a large and profitable scale.

Seen from above it has the appearance of a small village (see photo) and in its heyday supported up to 300 workers.

This was the first shore-based whaling station in the Antarctic region but more soon followed with similar stations built at Husvik, Stromness, Leith and Prince Olav.

Some 175,000 whales were caught and processed in the 60 year period of whaling around South Georgia.

Although interesting, we found the whaling station a bit depressing, a testament to man's greed and cruelty as well a monument to human endeavour and determination to succeed in a harsh environment.

|

| |

There is a good museum housed in the rennovated manager's villa with lots of information about not only whaling but the history of South Georgia's discovery and exploration plus some excellent natural history exhibits.

On the south shore of the bay a small cemetery lies nestled between a grassy slope and the sea, with a backdrop of towering mountains.

Most of the graves are of whalers and we were struck by how young many of them were when they perished.

Here lies Sir Ernest Shackleton, one of the great Antarctic explorers.

Perhaps best known for the incredible 800 mile boat journey undertaken with 5 other men from Elephant Island to the inhospitable south coast of South Georgia, followed by a trek across the unmapped icefields of the interior to seek help at Stromness whaling station, Shackleton had a special bond with this island.

His headstone, a simple but impressive block of rough hewn granite, is inscribed with a few well chosen words and the nine pointed star that was his personal symbol (see photo).

While the other graves are oriented east, Shackleton's points southward to the Antarctic continent.

Standing there beneath the scudding clouds with a cold wind blowing and the wild interior of South Georgia a few miles up the valley we paid silent tribute to this inspirational man.

Having had a few days to relax after the passage we are now ready to get moving again and plan to leave Grytviken tomorrow to make our way along the coast towards the western tip of the island...

There is a good museum housed in the rennovated manager's villa with lots of information about not only whaling but the history of South Georgia's discovery and exploration plus some excellent natural history exhibits.

On the south shore of the bay a small cemetery lies nestled between a grassy slope and the sea, with a backdrop of towering mountains.

Most of the graves are of whalers and we were struck by how young many of them were when they perished.

Here lies Sir Ernest Shackleton, one of the great Antarctic explorers.

Perhaps best known for the incredible 800 mile boat journey undertaken with 5 other men from Elephant Island to the inhospitable south coast of South Georgia, followed by a trek across the unmapped icefields of the interior to seek help at Stromness whaling station, Shackleton had a special bond with this island.

His headstone, a simple but impressive block of rough hewn granite, is inscribed with a few well chosen words and the nine pointed star that was his personal symbol (see photo).

While the other graves are oriented east, Shackleton's points southward to the Antarctic continent.

Standing there beneath the scudding clouds with a cold wind blowing and the wild interior of South Georgia a few miles up the valley we paid silent tribute to this inspirational man.

Having had a few days to relax after the passage we are now ready to get moving again and plan to leave Grytviken tomorrow to make our way along the coast towards the western tip of the island...

|

| |

January 19 2008

Prince Olav Harbour

|

It has been a week of contrasts and memorable experiences as we made our way along South Georgia's north coast towards the Bay of Isles.

Leaving Grytviken on what seemed like a calm, sunny afternoon we had an abrupt introduction to just how unpredictable the weather can be here.

We came around the point into 35 knots of northwest wind which was sending violent willywaws (gusts) scurrying across the water, whipping up spirals of salt spray like mini tornados.

Pelted by stinging hail we pounded into it, making for an anchorage called Maiviken which was happily only a few miles away.

Reaching the shelter of the bay between two long, green headlands we found ourselves in what seemed like a secret hideaway and tucked into a tiny cove amongst the rocks to escape from the swell.

By the time we had had a cup of tea the skies were clearing and we launched the dinghy to go exploring ashore.

Landing on a little gravel beach we negotiated our way past a number of fur seals and up into an area of hillocks covered in tussac grass where we found a small colony of gentoo penguins.

These are still our favourite penguins as they are such characters and there is never a dull moment at their colonies.

The chicks are already well grown and the feeding chases that we saw last summer in Antarctica were in full swing here.

Perhaps a way for parents to make sure they only feed their own chicks, rather than possible 'freeloaders', the chases take place at high speed through the colony whenever an adult returns from a fishing trip.

With wings outstretched for balance the parent sets off at a run with the chicks in hot pursuit, causing mayhem as they pass too close to their complaining neighbours.

Once satisfied, the adult stops and allows the chick to beg for its meal, a stream of regurgitated krill delivered directly into the chick's eager bill (see photo).

It has been a week of contrasts and memorable experiences as we made our way along South Georgia's north coast towards the Bay of Isles.

Leaving Grytviken on what seemed like a calm, sunny afternoon we had an abrupt introduction to just how unpredictable the weather can be here.

We came around the point into 35 knots of northwest wind which was sending violent willywaws (gusts) scurrying across the water, whipping up spirals of salt spray like mini tornados.

Pelted by stinging hail we pounded into it, making for an anchorage called Maiviken which was happily only a few miles away.

Reaching the shelter of the bay between two long, green headlands we found ourselves in what seemed like a secret hideaway and tucked into a tiny cove amongst the rocks to escape from the swell.

By the time we had had a cup of tea the skies were clearing and we launched the dinghy to go exploring ashore.

Landing on a little gravel beach we negotiated our way past a number of fur seals and up into an area of hillocks covered in tussac grass where we found a small colony of gentoo penguins.

These are still our favourite penguins as they are such characters and there is never a dull moment at their colonies.

The chicks are already well grown and the feeding chases that we saw last summer in Antarctica were in full swing here.

Perhaps a way for parents to make sure they only feed their own chicks, rather than possible 'freeloaders', the chases take place at high speed through the colony whenever an adult returns from a fishing trip.

With wings outstretched for balance the parent sets off at a run with the chicks in hot pursuit, causing mayhem as they pass too close to their complaining neighbours.

Once satisfied, the adult stops and allows the chick to beg for its meal, a stream of regurgitated krill delivered directly into the chick's eager bill (see photo).

|

| |

The forecast was for several days of strong winds so we pushed on the next morning to sail to Husvik about 12 miles away.

Deep within Stromness Bay, Husvik is the site of another old whaling station and offers a safe and well protected anchorage, one of only a handful along this stretch of coast.

It was a glorious morning and as we sped across the milky blue waters of Cumberland West Bay amid chunks of drifting ice calved from the Neumayer glacier we had incredible views back towards the Allardyce Mountains, their summits lost under a blanket of cloud (see photo).

About 5 miles offshore we could see a large tabular berg, an inaccessible island of ice, which was at least a mile long.

By mid afternoon we were setting our anchor off the derelict, rusting remains of the whaling station, just ahead of a squall that swept sheets of driving sleet down the valley.

In the morning bright sunshine lured us off on a long hike to reach a glacial lake a few miles away.

Away from the bright green moss, bog and tussac grass of the coastal region the landscape appears almost lunar with jagged peaks of black rock presiding over scree filled valleys.

The higher we climbed the stronger the wind became, funneling through the pass, until we reached a col overlooking a glacier.

Blasts of buffeting wind literally knocked us off our feet and we estimated it to be a good 60 knots -

another exciting South Georgia experience!

The forecast was for several days of strong winds so we pushed on the next morning to sail to Husvik about 12 miles away.

Deep within Stromness Bay, Husvik is the site of another old whaling station and offers a safe and well protected anchorage, one of only a handful along this stretch of coast.

It was a glorious morning and as we sped across the milky blue waters of Cumberland West Bay amid chunks of drifting ice calved from the Neumayer glacier we had incredible views back towards the Allardyce Mountains, their summits lost under a blanket of cloud (see photo).

About 5 miles offshore we could see a large tabular berg, an inaccessible island of ice, which was at least a mile long.

By mid afternoon we were setting our anchor off the derelict, rusting remains of the whaling station, just ahead of a squall that swept sheets of driving sleet down the valley.

In the morning bright sunshine lured us off on a long hike to reach a glacial lake a few miles away.

Away from the bright green moss, bog and tussac grass of the coastal region the landscape appears almost lunar with jagged peaks of black rock presiding over scree filled valleys.

The higher we climbed the stronger the wind became, funneling through the pass, until we reached a col overlooking a glacier.

Blasts of buffeting wind literally knocked us off our feet and we estimated it to be a good 60 knots -

another exciting South Georgia experience!

|

| |

When the weather calmed down we took the opportunity to visit Hercules Bay, an exposed anchorage that is often subject to a large swell.

In swirling fog we nudged into the bay, an impressive amphitheater of almost sheer cliffs, great folds of rock with a few scant clumps of vegetation clinging in gullies.

A mare's tail waterfall cascades down in three long strands to a tiny rocky beach, where we anchored close to the shore (see photo).

For once the ever present wailing and yelping of seals was drowned out by the raucous chattering of Macaroni penguins and their noisy calls seemed to fill the bay, echoing off the cliffs.

Their colony was spread up a precipitous slope and the nests were hidden amongst clumps of tussac grass, although we caught a glimpse of several downy chicks.

All along the water's edge birds were standing to preen as they came out of the sea onto the high rocks, and we drifted along in the dinghy to have our first close look at this species of penguin.

But the highlight was spotting several Light-mantled sooty albatross nests perched on cliff ledges near the mouth of the bay and we decided to see if we could reach them overland.

When the weather calmed down we took the opportunity to visit Hercules Bay, an exposed anchorage that is often subject to a large swell.

In swirling fog we nudged into the bay, an impressive amphitheater of almost sheer cliffs, great folds of rock with a few scant clumps of vegetation clinging in gullies.

A mare's tail waterfall cascades down in three long strands to a tiny rocky beach, where we anchored close to the shore (see photo).

For once the ever present wailing and yelping of seals was drowned out by the raucous chattering of Macaroni penguins and their noisy calls seemed to fill the bay, echoing off the cliffs.

Their colony was spread up a precipitous slope and the nests were hidden amongst clumps of tussac grass, although we caught a glimpse of several downy chicks.

All along the water's edge birds were standing to preen as they came out of the sea onto the high rocks, and we drifted along in the dinghy to have our first close look at this species of penguin.

But the highlight was spotting several Light-mantled sooty albatross nests perched on cliff ledges near the mouth of the bay and we decided to see if we could reach them overland.

|

| |

The anchorage was too tentative to leave the boat unattended so we took turns to be dropped off ashore and climbed up a steep scree slope to a saddle from which we could access a grassy ridge above the cliffs.

The albatrosses were nesting towards the end of a small point well hidden amongst the clumps of tussac grass and finding them was like discovering a special secret.

Light-mantled sooty albatrosses do not nest in large colonies but in small, scattered groups or even singly, making them harder to observe.

This group consisted of 4 nesting birds, each on a low pedestal nest of mud and grass.

The birds are beautiful, with a partial white eye ring and a violet-blue coloured stripe on the bill standing out against the soft, chocolate brown head.

The dark plummage fades into a pale grey neck and back (see photo).

We saw chicks at several nests which we guessed to be about a week old, little tan brown fluff balls burrowing under the warmth of the adults when they stood to stretch or preen.

This species breeds on remote islands all around the Southern Ocean with an estimated total breeding population of just under 60,000 individuals.

Little seems to be known about population trends but where studied, declines in numbers have been noted and the species is listed as 'Near Threatened'.

As with so many albatross species, there are reports of mortality associated with both tuna longlining and unregulated fishing for Patagonian Toothfish (Chilean Sea Bass)

For more information on all albatross species and the threats that face them visit www.savethealbatross.net

The anchorage was too tentative to leave the boat unattended so we took turns to be dropped off ashore and climbed up a steep scree slope to a saddle from which we could access a grassy ridge above the cliffs.

The albatrosses were nesting towards the end of a small point well hidden amongst the clumps of tussac grass and finding them was like discovering a special secret.

Light-mantled sooty albatrosses do not nest in large colonies but in small, scattered groups or even singly, making them harder to observe.

This group consisted of 4 nesting birds, each on a low pedestal nest of mud and grass.

The birds are beautiful, with a partial white eye ring and a violet-blue coloured stripe on the bill standing out against the soft, chocolate brown head.

The dark plummage fades into a pale grey neck and back (see photo).

We saw chicks at several nests which we guessed to be about a week old, little tan brown fluff balls burrowing under the warmth of the adults when they stood to stretch or preen.

This species breeds on remote islands all around the Southern Ocean with an estimated total breeding population of just under 60,000 individuals.

Little seems to be known about population trends but where studied, declines in numbers have been noted and the species is listed as 'Near Threatened'.

As with so many albatross species, there are reports of mortality associated with both tuna longlining and unregulated fishing for Patagonian Toothfish (Chilean Sea Bass)

For more information on all albatross species and the threats that face them visit www.savethealbatross.net

|

| |

|

The anchorage in Hercules Bay was not suitable for an overnight stop due to the onshore wind and swell so we sailed on a few miles to Fortuna Bay, a fjord cutting about 3 miles into the island with the Konig Glacier at its head.

At last light we found a sheltered cove on the east side of the bay beneath towering peaks.

It was snowing heavily for most of the next day but late in the afternoon we got ashore for a few hours and watched male elephant seals sparring on the beach.

Today we sailed on up the coast to Prince Olav Harbour, the site of another whaling station, which offers good shelter and is close to the Bay of Isles where we plan to spend most of the coming week....

|

| |

January 27 2008

Bay of Isles

|

For us the Wandering albatross is the greatest of all seabirds, symbolising the wild freedom of the open ocean.

One of the highlights of visiting South Georgia is the opportunity to see these magnificent birds at their breeding sites.

We have spent this week around the Bay of Isles where Prion Island is one of the few accessible wanderer nesting areas, the main breeding islands, Albatross and Bird, being closed to all but researchers.

There is no proper anchorage at Prion island with poor holding in an exposed location so at night and during bad weather we made for the shelter of either Prince Olav bay to the east or Rosita to the west.

Except for two calm days the weather has been dreadful.

Over a 48 hour period we weathered 2 gales in Prince Olav which brought driving snow and vicious williwaws of at least 60 knots that buffeted us and whipped the sea into a frenzy.

We were sharing the anchorage with another yacht (see photo) but the conditons made it impossible to launch our dinghies in order to get together or get ashore.

For us the Wandering albatross is the greatest of all seabirds, symbolising the wild freedom of the open ocean.

One of the highlights of visiting South Georgia is the opportunity to see these magnificent birds at their breeding sites.

We have spent this week around the Bay of Isles where Prion Island is one of the few accessible wanderer nesting areas, the main breeding islands, Albatross and Bird, being closed to all but researchers.

There is no proper anchorage at Prion island with poor holding in an exposed location so at night and during bad weather we made for the shelter of either Prince Olav bay to the east or Rosita to the west.

Except for two calm days the weather has been dreadful.

Over a 48 hour period we weathered 2 gales in Prince Olav which brought driving snow and vicious williwaws of at least 60 knots that buffeted us and whipped the sea into a frenzy.

We were sharing the anchorage with another yacht (see photo) but the conditons made it impossible to launch our dinghies in order to get together or get ashore.

|

| |

But the challenge of getting there just made visiting Prion all the more special and meeting our first Wandering albatross up close is something we will never forget.

The island is small, perhaps a kilometre long by a half wide, with slopes of dense tussac grass leading up to a central plateau where the albatrosses breed.

There are just over 30 nests on the island this season and wherever we looked the white shapes of birds sitting patiently on their well-spaced, mounded nests of grass (see photo) stood out amid the tussac.

Wanderers incubate their single egg for about 2 1/2 months, males and females sharing the task more or less equally.

While one bird is taking its turn at the nest the other is out at sea for up to 20 days on long foraging trips.

Once the chick hatches, sometime in early March, the birds make shorter trips and return more frequently to feed the chick.

Due to the exceptionally long chick rearing period, close to 280 days, the Wandering albatross can only breed every second year, spending the time in between ranging vast distances at sea.

But the challenge of getting there just made visiting Prion all the more special and meeting our first Wandering albatross up close is something we will never forget.

The island is small, perhaps a kilometre long by a half wide, with slopes of dense tussac grass leading up to a central plateau where the albatrosses breed.

There are just over 30 nests on the island this season and wherever we looked the white shapes of birds sitting patiently on their well-spaced, mounded nests of grass (see photo) stood out amid the tussac.

Wanderers incubate their single egg for about 2 1/2 months, males and females sharing the task more or less equally.

While one bird is taking its turn at the nest the other is out at sea for up to 20 days on long foraging trips.

Once the chick hatches, sometime in early March, the birds make shorter trips and return more frequently to feed the chick.

Due to the exceptionally long chick rearing period, close to 280 days, the Wandering albatross can only breed every second year, spending the time in between ranging vast distances at sea.

|

| |

Perhaps the most remarkable behaviour of these superlative birds is their complex courtship display, performed primarily during initial pair-bond formation.

It was a magical and moving experience to sit alone on the grassy summit of Prion island watching the beautiful birds engage in these rituals and we felt priviliged to be there.

Males are believed to return to the colony of their birth for a number of seasons before selecting a nest site at 8-10 years old.

Sitting or standing at their display nest, they try to attract a female by stretching their necks and calling to the sky with a rapid snapping of the bill (see photo).

It is the females that seem to decide upon a mate and they appear rather fussy - but choosing the right partner is very important as wanderers usually mate for life.

They soar overhead countless times before coming in to land, often in an awkward and ungainly manner.

Once on the ground the birds move around on their large, webbed feet, stalking through the long grass with backs hunched and necks outstretched.

In this stance they approach each other to begin their elegant courtship dance, slapping their feet as they go.

Perhaps the most remarkable behaviour of these superlative birds is their complex courtship display, performed primarily during initial pair-bond formation.

It was a magical and moving experience to sit alone on the grassy summit of Prion island watching the beautiful birds engage in these rituals and we felt priviliged to be there.

Males are believed to return to the colony of their birth for a number of seasons before selecting a nest site at 8-10 years old.

Sitting or standing at their display nest, they try to attract a female by stretching their necks and calling to the sky with a rapid snapping of the bill (see photo).

It is the females that seem to decide upon a mate and they appear rather fussy - but choosing the right partner is very important as wanderers usually mate for life.

They soar overhead countless times before coming in to land, often in an awkward and ungainly manner.

Once on the ground the birds move around on their large, webbed feet, stalking through the long grass with backs hunched and necks outstretched.

In this stance they approach each other to begin their elegant courtship dance, slapping their feet as they go.

|

| |

Like partners about to begin a waltz, the two birds stand close together facing each other.

Starting to perform a seemingly choreographed sequence of head movements, they bow forward with their necks parallel to the ground then retract them with an abrupt movement until their bills are touching their breasts and their necks are curved.

Much high speed vibration of the bill and audible snapping accompanies this phase and at times the birds seemed quite ecstatic.

All of a sudden the male arcs his wings out in a stiff curve with the undersurface forward and swings his head up with a loud, trilling whine.

Sometimes at this stage a third bird interfered with the performance, competing for attention - females tried to join the dance but males tended to end it and we witnessed several short fights between males, a blur of angry snapping bills and tangled wings.

But the complete dance, played out in perfect harmony, is a joy to behold and we were lucky enough to see it happen several times.

As the male circles with wings outstretched, the pair touch bills in a gentle and intimate gesture and soon the female spreads her wings also (see photo).

Pirouetting around each other they lift their feet in exaggerated steps, vocalise and clap their bills and continue to bow and stretch their necks.

On one occasion this went on for over 10 minutes before the birds folded their wings and settled down in companionable proximity.

It can take years for the pair-bond to form prior to breeding and this pair appeared very fond of each other, performing the complete dance more than once.

We liked to think that their bond was close to being final while the other, incomplete, dances may have been indicative of younger, less experienced birds.

The hours we spent with these beautiful birds were unforgettable, a unique glimpse into the secrets of their lives.

Like partners about to begin a waltz, the two birds stand close together facing each other.

Starting to perform a seemingly choreographed sequence of head movements, they bow forward with their necks parallel to the ground then retract them with an abrupt movement until their bills are touching their breasts and their necks are curved.

Much high speed vibration of the bill and audible snapping accompanies this phase and at times the birds seemed quite ecstatic.

All of a sudden the male arcs his wings out in a stiff curve with the undersurface forward and swings his head up with a loud, trilling whine.

Sometimes at this stage a third bird interfered with the performance, competing for attention - females tried to join the dance but males tended to end it and we witnessed several short fights between males, a blur of angry snapping bills and tangled wings.

But the complete dance, played out in perfect harmony, is a joy to behold and we were lucky enough to see it happen several times.

As the male circles with wings outstretched, the pair touch bills in a gentle and intimate gesture and soon the female spreads her wings also (see photo).

Pirouetting around each other they lift their feet in exaggerated steps, vocalise and clap their bills and continue to bow and stretch their necks.

On one occasion this went on for over 10 minutes before the birds folded their wings and settled down in companionable proximity.

It can take years for the pair-bond to form prior to breeding and this pair appeared very fond of each other, performing the complete dance more than once.

We liked to think that their bond was close to being final while the other, incomplete, dances may have been indicative of younger, less experienced birds.

The hours we spent with these beautiful birds were unforgettable, a unique glimpse into the secrets of their lives.

|

| |

In the air, wandering albatrosses are gliding machines (see photo) with a wingspan greater than any other bird.

These long, narrow wings are unsuited to flapping flight, which for wanderers wastes a lot of energy, and they rely on the wind to power their lengthy flights at impressive speed.

Using satellite-transmitters and miniature GPS loggers, scientists have discovered amazing facts about these ocean travellers.

One bird was recorded covering 20,000 km in 103 days and others have been shown to circumnavigate the Southern Ocean without ever touching land.

Even during the breeding season some birds cover many thousands of kms on a single foraging trip.

Sadly, it is this very wanderlust that makes it so difficult to protect them from illegal or unregulated long-line fisheries.

Birds from South Georgia have been found to feed in the productive coastal waters of South America, South Africa and even Australia, where they are often caught on long-line hooks.

In the last 20 years wandering albatross numbers have dropped by about 30% and, of more concern, the rate of decline has accelerated in the last decade.

It seems inconceivable that these incredible and special birds may one day cease to roam the Southern Ocean.

But until all fishing vessels adopt the simple and inexpensive bycatch mitigation measures that have been proven to work in well managed fisheries, the future of the wandering albatross, and indeed most albatross species, hangs in the balance.

An international campaign to 'Save the Albatross' is currently underway with a focus on introducing effective mitigation measures in key fishing areas.

For more information on what is being done and how you can help, visit www.savethealbatross.net

In the air, wandering albatrosses are gliding machines (see photo) with a wingspan greater than any other bird.

These long, narrow wings are unsuited to flapping flight, which for wanderers wastes a lot of energy, and they rely on the wind to power their lengthy flights at impressive speed.

Using satellite-transmitters and miniature GPS loggers, scientists have discovered amazing facts about these ocean travellers.

One bird was recorded covering 20,000 km in 103 days and others have been shown to circumnavigate the Southern Ocean without ever touching land.

Even during the breeding season some birds cover many thousands of kms on a single foraging trip.

Sadly, it is this very wanderlust that makes it so difficult to protect them from illegal or unregulated long-line fisheries.

Birds from South Georgia have been found to feed in the productive coastal waters of South America, South Africa and even Australia, where they are often caught on long-line hooks.

In the last 20 years wandering albatross numbers have dropped by about 30% and, of more concern, the rate of decline has accelerated in the last decade.

It seems inconceivable that these incredible and special birds may one day cease to roam the Southern Ocean.

But until all fishing vessels adopt the simple and inexpensive bycatch mitigation measures that have been proven to work in well managed fisheries, the future of the wandering albatross, and indeed most albatross species, hangs in the balance.

An international campaign to 'Save the Albatross' is currently underway with a focus on introducing effective mitigation measures in key fishing areas.

For more information on what is being done and how you can help, visit www.savethealbatross.net

|

| |

February 1 2008

|

South Georgia doesn't win any prizes for its weather but on a clear day there is nowhere else like it.

After endless mist, rain and low grey clouds it was wonderful to wake up one morning to a glittering world under blue skies.

Sailing to Salisbury Plain on the south shore of the Bay of Isles (see photo) we danced across a turquoise sea against a backdrop of distant snow-capped peaks.

Glaciers wind down from the inland icefields like great white rivers and a few bergs of ice blue were aground amongst the islands.

The anchorage at Salisbury Plain is little more than an open roadstead with deep water right up to the gravel beach.

Despite a sudden 30 knots of wind howling down the Grace glacier we found a reasonable spot to drop the hook in 60 feet of water and launch the dinghy.

Landing through a bit of surf we were greeted by scattered groups of king penguins, regal in their perfect plummage, and the inevitable fur seals, growling and snarling in protest at our presence.

Although there were fewer than elsewhere, they seemed particularly agressive, making threatening lunges at the dinghy as they emerged from the water.

Friends had their dinghy punctured by fur seals so we decided not to take any chances, instead taking turns to visit the nearby colony of king penguins, while one of us stayed on the beach to guard the dinghy.

South Georgia doesn't win any prizes for its weather but on a clear day there is nowhere else like it.

After endless mist, rain and low grey clouds it was wonderful to wake up one morning to a glittering world under blue skies.

Sailing to Salisbury Plain on the south shore of the Bay of Isles (see photo) we danced across a turquoise sea against a backdrop of distant snow-capped peaks.

Glaciers wind down from the inland icefields like great white rivers and a few bergs of ice blue were aground amongst the islands.

The anchorage at Salisbury Plain is little more than an open roadstead with deep water right up to the gravel beach.

Despite a sudden 30 knots of wind howling down the Grace glacier we found a reasonable spot to drop the hook in 60 feet of water and launch the dinghy.

Landing through a bit of surf we were greeted by scattered groups of king penguins, regal in their perfect plummage, and the inevitable fur seals, growling and snarling in protest at our presence.

Although there were fewer than elsewhere, they seemed particularly agressive, making threatening lunges at the dinghy as they emerged from the water.

Friends had their dinghy punctured by fur seals so we decided not to take any chances, instead taking turns to visit the nearby colony of king penguins, while one of us stayed on the beach to guard the dinghy.

|

| |

The scenery was spectacular on the half mile walk along the beach with the mountains etched against the sky and tendrils of mist creeping down the glaciers.

The king colony here is the second largest in South Georgia with an estimated 60,000 breeding pairs and many more birds standing in disconsolate groups as they moult.

The closer we got, the more penguins there were until at last we had a clear view of the main colony.

It was a fantastic sight with tight packed birds stretching across the plain as far as the eye could see (see photo), their bright orange ear patches and golden throats bobbing and swaying like a field of sunflowers.

The noise was also quite something with countless adult birds trumpeting and chicks whistling as they begged for a feed.

Kings are unique amongst penguins as their breeding cycle lasts over a year.

Chicks remain on land for their first winter being fed only occasionally by their parents who must forage far out at sea to find sufficient food.

At large colonies like this almost every phase of the cycle can be seen.

Courting birds strutting in aristocratic pairs on the periphery of the main colony where incubating birds stand with eggs on their feet, bulging like pot-bellies beneath their brood pouches.

Last year's chicks are at all stages of fledging out of their thick, brown, teddy-bear down.

They are so large and so different from their elegant parents that the early explorers thought they were a separate species and called them "Woolly" penguins.

The scenery was spectacular on the half mile walk along the beach with the mountains etched against the sky and tendrils of mist creeping down the glaciers.

The king colony here is the second largest in South Georgia with an estimated 60,000 breeding pairs and many more birds standing in disconsolate groups as they moult.

The closer we got, the more penguins there were until at last we had a clear view of the main colony.

It was a fantastic sight with tight packed birds stretching across the plain as far as the eye could see (see photo), their bright orange ear patches and golden throats bobbing and swaying like a field of sunflowers.

The noise was also quite something with countless adult birds trumpeting and chicks whistling as they begged for a feed.

Kings are unique amongst penguins as their breeding cycle lasts over a year.

Chicks remain on land for their first winter being fed only occasionally by their parents who must forage far out at sea to find sufficient food.

At large colonies like this almost every phase of the cycle can be seen.

Courting birds strutting in aristocratic pairs on the periphery of the main colony where incubating birds stand with eggs on their feet, bulging like pot-bellies beneath their brood pouches.

Last year's chicks are at all stages of fledging out of their thick, brown, teddy-bear down.

They are so large and so different from their elegant parents that the early explorers thought they were a separate species and called them "Woolly" penguins.

|

| |

About 48,000 pairs, approximately half the world population, of grey-headed albatross breed at South Georgia and we were hoping to see these beautiful birds at their nests.

All the colonies are found in the north western part of the island where the birds tend to nest on inaccessible cliffs.

As we sailed along the coast we spotted several colonies high up on steep tussac slopes that were impossible to approach.

But there is one anchorage at the far west of the island where a few small groups of grey-headed albatrosses breed on a low isthmus.

From the landing beach an unpleasant trek through a fur seal infested, muddy quagmire took us to a vantage point overlooking several nests and it was thrilling to see this species up close.

The adult birds are very pretty with soft, ashy-grey heads and bright yellow stripes on their black bills (see photo).

About 48,000 pairs, approximately half the world population, of grey-headed albatross breed at South Georgia and we were hoping to see these beautiful birds at their nests.

All the colonies are found in the north western part of the island where the birds tend to nest on inaccessible cliffs.

As we sailed along the coast we spotted several colonies high up on steep tussac slopes that were impossible to approach.

But there is one anchorage at the far west of the island where a few small groups of grey-headed albatrosses breed on a low isthmus.

From the landing beach an unpleasant trek through a fur seal infested, muddy quagmire took us to a vantage point overlooking several nests and it was thrilling to see this species up close.

The adult birds are very pretty with soft, ashy-grey heads and bright yellow stripes on their black bills (see photo).

|

| |

The neat, round pedestal nests were perched in precarious positions amid dense tussac grass at the top of a small cliff.

A fluffy chick sat proud on each nest, all pale grey down with bright black eyes and bills (see photo).

Perhaps 3 or 4 weeks old, they are already large, dominating the nest as they await a returning parent to bring the next feed.

The adults soared with easy grace along the edge of the cliff at eye level before coming in to land, not always easy in the tangle of tussac grass.

The expectant chick greets the parent with an eager clicking of the bill and a rich stream of regurgitated oil is delivered quickly.

We knew this would be the only chance we had to watch these lovely birds and savoured the experience, lingering until the fading light forced us to return to the boat.

During the breeding season grey-headed albatrosses tend to forage with a few hundred kilometers of their colonies but when not raising a chick they disperse around the Southern Ocean.

Birds from South Georgia have been recorded circling the globe, one in an astonishing 46 days.

They are not averse to scavenging and often attempt to steal bait from fishing hooks, meaning many thousands die each year in long line fisheries.

Like so many albatross species, grey-headed albatrosses have suffered a serious decline in numbers over the past 30 years and are now listed as "vulnerable".

For more information visit www.savethealbatross.net

The neat, round pedestal nests were perched in precarious positions amid dense tussac grass at the top of a small cliff.

A fluffy chick sat proud on each nest, all pale grey down with bright black eyes and bills (see photo).

Perhaps 3 or 4 weeks old, they are already large, dominating the nest as they await a returning parent to bring the next feed.

The adults soared with easy grace along the edge of the cliff at eye level before coming in to land, not always easy in the tangle of tussac grass.

The expectant chick greets the parent with an eager clicking of the bill and a rich stream of regurgitated oil is delivered quickly.

We knew this would be the only chance we had to watch these lovely birds and savoured the experience, lingering until the fading light forced us to return to the boat.

During the breeding season grey-headed albatrosses tend to forage with a few hundred kilometers of their colonies but when not raising a chick they disperse around the Southern Ocean.

Birds from South Georgia have been recorded circling the globe, one in an astonishing 46 days.

They are not averse to scavenging and often attempt to steal bait from fishing hooks, meaning many thousands die each year in long line fisheries.

Like so many albatross species, grey-headed albatrosses have suffered a serious decline in numbers over the past 30 years and are now listed as "vulnerable".

For more information visit www.savethealbatross.net

|

| |

February 10 2008

South Coast

|

As well as spending time with the birds in South Georgia, we had an ambition to sail down the rugged and inhospitable south coast.

This wild coast bears the full brunt of Southern Ocean gales, is poorly charted and offers few sheltered anchorages.

It is rarely visited, which makes it all the more alluring.

When the forecast promised a few days of settled weather we decided to try it.

On a steel grey day we beat 15 miles west from Right Whale Bay to reach Bird Sound, a narrow channel separating the main island from Bird Island (see photo).

The passage is encumbered by reefs and rocks where the ceaseless Southern Ocean swell peaks and crashes.

From a distance all we could see through binoculars was seething white water, black rocks and ice.

But as we navigated towards a waypoint at the entrance to the sound we began to make out the safe route through.

The gap was barely 100m wide with the steep shores of Bird Island to starboard and surging swell breaking over a reef to port.

As well as spending time with the birds in South Georgia, we had an ambition to sail down the rugged and inhospitable south coast.

This wild coast bears the full brunt of Southern Ocean gales, is poorly charted and offers few sheltered anchorages.

It is rarely visited, which makes it all the more alluring.

When the forecast promised a few days of settled weather we decided to try it.

On a steel grey day we beat 15 miles west from Right Whale Bay to reach Bird Sound, a narrow channel separating the main island from Bird Island (see photo).

The passage is encumbered by reefs and rocks where the ceaseless Southern Ocean swell peaks and crashes.

From a distance all we could see through binoculars was seething white water, black rocks and ice.

But as we navigated towards a waypoint at the entrance to the sound we began to make out the safe route through.

The gap was barely 100m wide with the steep shores of Bird Island to starboard and surging swell breaking over a reef to port.

|

| |

It was a relief to reach the other side and in a light westerly breeze we set the sails again and picked a slow course around Cape Paryadin towards Undine Harbour.

The clouds were so low they seemed to brush the mast-top, swirling thick around the preciptous cliffs.

Turbulent seas sucked at hungry rocks that stretched some distance offshore and countless magnificent bergs were stranded on the reefs and shoals (see photo).

This was the essence of the South Georgia we had always imagined and the primordial scene thrilled us.

With a choice of 3 bays, Undine Harbour provides shelter in almost all conditions, the last such anchorage for 100 miles.

Surrounded by rolling hills cloaked in verdant tussac grass it seemed an oasis amid the forbidding mass of rock and ice.

In the distance, on the green slopes, the distinctive white dots of wandering albatrosses on their nests stood out and it was nice to know they were there.

It was a relief to reach the other side and in a light westerly breeze we set the sails again and picked a slow course around Cape Paryadin towards Undine Harbour.

The clouds were so low they seemed to brush the mast-top, swirling thick around the preciptous cliffs.

Turbulent seas sucked at hungry rocks that stretched some distance offshore and countless magnificent bergs were stranded on the reefs and shoals (see photo).

This was the essence of the South Georgia we had always imagined and the primordial scene thrilled us.

With a choice of 3 bays, Undine Harbour provides shelter in almost all conditions, the last such anchorage for 100 miles.

Surrounded by rolling hills cloaked in verdant tussac grass it seemed an oasis amid the forbidding mass of rock and ice.

In the distance, on the green slopes, the distinctive white dots of wandering albatrosses on their nests stood out and it was nice to know they were there.

|

| |

A highlight of the south coast is King Haakon bay where Sir Ernest Shackleton's shadow lingers.

At the entrance to this long fjord, which cuts 8 miles into the interior, Cape Rosa has a special significance.

It was here that after their gruelling journey across 800 miles of freezing, stormy seas in the 25' open boat, James Caird, Shackleton and his 5 brave companions managed to reach the safety of a tiny cove (see photo).

Conditions were remarkably calm, allowing us to heave-to outside the cove and take turns to row in through the narrow cut in the cliffs.

The ever present swell was surging over the numerous rocks off the entrance and rushing up the little boulder beach where we landed.

It was easy to imagine the relief the men felt as they stumbled ashore, falling to their knees to quench their thirst in a stream that still burbles over the stones.

A shallow cave, with just enough room for 6 men to lie down, provided shelter while they regained their strength.

Their spirits remain in that place and to be there was a moving experience, the fulfillment of a long-held personal dream.

A highlight of the south coast is King Haakon bay where Sir Ernest Shackleton's shadow lingers.

At the entrance to this long fjord, which cuts 8 miles into the interior, Cape Rosa has a special significance.

It was here that after their gruelling journey across 800 miles of freezing, stormy seas in the 25' open boat, James Caird, Shackleton and his 5 brave companions managed to reach the safety of a tiny cove (see photo).

Conditions were remarkably calm, allowing us to heave-to outside the cove and take turns to row in through the narrow cut in the cliffs.

The ever present swell was surging over the numerous rocks off the entrance and rushing up the little boulder beach where we landed.

It was easy to imagine the relief the men felt as they stumbled ashore, falling to their knees to quench their thirst in a stream that still burbles over the stones.

A shallow cave, with just enough room for 6 men to lie down, provided shelter while they regained their strength.

Their spirits remain in that place and to be there was a moving experience, the fulfillment of a long-held personal dream.

|

| |

As we sailed to the head of King Haakon Bay to find an anchorage for the night, the sun broke through the ceiling of cloud for the first time in a week, adding to the grandeur around us.

Ragged scraps of blue sky appeared and the light shone on the tumbling glaciers that spill down the sheer rock walls.

When Shackleton and his party sailed up the fjord over 90 years ago they counted 12 glaciers reaching the sea.

The glaciers are still there, but only two now come all the way to the water.

The men beached the James Caird for the final time at the head of the bay, protected by a rounded headland.

They turned the boat upside down on a low wall of stones to create a shelter at what became known as Peggotty Bluff.

From here, Shackelton, Worsley and Crean set out across unmapped ice-fields to seek help at Stromness whaling station on the other side of the island.

We anchored in the lee of the diminutive Vincent Islands, dwarfed by the surroundings (see photo) and walked along the stoney beach to Peggotty Bluff, another emotive spot.

From the top we had a sweeping view back towards the glaciers and the low ice col, now called Shackleton Gap, over which the men trekked with nails in their boots instead of crampons, a 50' length of rope and a modified adze as an ice-axe.

As we sailed to the head of King Haakon Bay to find an anchorage for the night, the sun broke through the ceiling of cloud for the first time in a week, adding to the grandeur around us.

Ragged scraps of blue sky appeared and the light shone on the tumbling glaciers that spill down the sheer rock walls.

When Shackleton and his party sailed up the fjord over 90 years ago they counted 12 glaciers reaching the sea.

The glaciers are still there, but only two now come all the way to the water.

The men beached the James Caird for the final time at the head of the bay, protected by a rounded headland.

They turned the boat upside down on a low wall of stones to create a shelter at what became known as Peggotty Bluff.

From here, Shackelton, Worsley and Crean set out across unmapped ice-fields to seek help at Stromness whaling station on the other side of the island.

We anchored in the lee of the diminutive Vincent Islands, dwarfed by the surroundings (see photo) and walked along the stoney beach to Peggotty Bluff, another emotive spot.

From the top we had a sweeping view back towards the glaciers and the low ice col, now called Shackleton Gap, over which the men trekked with nails in their boots instead of crampons, a 50' length of rope and a modified adze as an ice-axe.

|

| |

The weather forecast remained promising, with unusually light winds presenting an opportunity to continue down the south coast and explore a few potential anchorages.

From here on we had no information other than sparse descriptions in the Admiralty Pilot, peppered with cautions, and no detail on the chart.

In a world where little remains to be discovered it was exciting to venture into relatively unknown waters.

On another grey day with almost no wind we motor-sailed 20 miles around the Nunez peninsula to reach Holmestrand at the foot of the mighty Esmark glacier, the largest in South Georgia.

The approach was a mass of '+' symbols on the chart which proved to be easily visible rocks and islets.

Although we kept a sharp lookout for underwater dangers the only real challenge was negotiating a thick swathe of ice fragments, shed by the glacier, that blocked the entrance (see photo).

Pushing through to reach open water we were delighted to find a beautiful bay encircled by a long crescent of black sand and protected from all but south east winds.

It was a great surprise, like discovering a secret hideaway, and we spent the afternoon walking ashore and visiting a small colony of king penguins.

The weather forecast remained promising, with unusually light winds presenting an opportunity to continue down the south coast and explore a few potential anchorages.

From here on we had no information other than sparse descriptions in the Admiralty Pilot, peppered with cautions, and no detail on the chart.

In a world where little remains to be discovered it was exciting to venture into relatively unknown waters.

On another grey day with almost no wind we motor-sailed 20 miles around the Nunez peninsula to reach Holmestrand at the foot of the mighty Esmark glacier, the largest in South Georgia.

The approach was a mass of '+' symbols on the chart which proved to be easily visible rocks and islets.

Although we kept a sharp lookout for underwater dangers the only real challenge was negotiating a thick swathe of ice fragments, shed by the glacier, that blocked the entrance (see photo).

Pushing through to reach open water we were delighted to find a beautiful bay encircled by a long crescent of black sand and protected from all but south east winds.

It was a great surprise, like discovering a secret hideaway, and we spent the afternoon walking ashore and visiting a small colony of king penguins.

|

| |

We were tempted to linger there the next day but the latest GRIB file was showing a strong depression forming 2 days hence that would bring 50 knot winds from the south - not a time to be caught out on this remote coast.

In what seemed akin to the 'calm before the storm' we motored south in glassy seas, enjoying a brief glimpse of spectacular scenery.

Glacier after glacier poured down from the ice-fields that cover a large area of South Georgia, all ending in the sea.

On the horizon, enormous tabular bergs glinted blue-white in distant sunshine, an archipelago of ice.

Everywhere we looked we saw wildlife, with storm petrels fluttering close to the surface, seals cavorting around the bow and, best of all, several sightings of whales, both Southern Right and Humpback.

A minor indent on the chart was a bay called Trollhul where we were hoping to stop, but until we arrived we doubted whether it was an overnight anchorage as it is wide open to the prevailing south west swell.

We were in luck, however, as not only did the bay offer an excellent anchorage in the light conditions, but the skies were clearing rapidly and by the time we had rowed ashore golden evening light bathed the glacier and the peaks of the Salvesen range were revealed in all their glory (see photo).

We spent a magical few hours watching the sunset as gentoo penguins waddled past.

Overnight the wind inevitably picked up but even doing anchor watch in the cockpit was a pleasure with stars arcing bright overhead and the snow-capped mountains silhouetted against a midnight-blue sky.

We were tempted to linger there the next day but the latest GRIB file was showing a strong depression forming 2 days hence that would bring 50 knot winds from the south - not a time to be caught out on this remote coast.

In what seemed akin to the 'calm before the storm' we motored south in glassy seas, enjoying a brief glimpse of spectacular scenery.

Glacier after glacier poured down from the ice-fields that cover a large area of South Georgia, all ending in the sea.

On the horizon, enormous tabular bergs glinted blue-white in distant sunshine, an archipelago of ice.

Everywhere we looked we saw wildlife, with storm petrels fluttering close to the surface, seals cavorting around the bow and, best of all, several sightings of whales, both Southern Right and Humpback.

A minor indent on the chart was a bay called Trollhul where we were hoping to stop, but until we arrived we doubted whether it was an overnight anchorage as it is wide open to the prevailing south west swell.

We were in luck, however, as not only did the bay offer an excellent anchorage in the light conditions, but the skies were clearing rapidly and by the time we had rowed ashore golden evening light bathed the glacier and the peaks of the Salvesen range were revealed in all their glory (see photo).

We spent a magical few hours watching the sunset as gentoo penguins waddled past.

Overnight the wind inevitably picked up but even doing anchor watch in the cockpit was a pleasure with stars arcing bright overhead and the snow-capped mountains silhouetted against a midnight-blue sky.

|

| |

Early next morning we set sail for Larsen Harbour, 15 miles away, beating into a moderate north east breeze (see photo).

Cape Disappointment loomed to port, named by Captain Cook because it proved South Georgia to be an island and not the mythical "Terra Australis Incognita" for which he was searching.